The Nude Male and Einfühlung in the 21st Century

The nude male has been present in the visual arts, at least since the time of Greek culture, in both painting and sculpture. He has been depicted as a heroic figure, a mythological figure, a warrior, a mischievous sexual adventurer, and at times a tragic suffering victim of oppression. In each case he is usually anatomically idealized with prominent musculature, and in almost all cases he is depicted as active—either engaged in some heroic activity where his physical prowess is brought into play, or about to be realized. Even when depicted in chains he is, as a human animal, shown as strong and active. When the nude male is in contemplation he is still in an active process, and interestingly he is still adorned with idealized musculature. This leads one to believe that the very essence of maleness requires the development of a well toned physique. Most of the time the nude has been used to convey an idea or a feeling, and both genders have been included in this pursuit. However, the nude male began to disappear from the visual arts around the turn of the 19th or early 20th century. In the second half of the 20th century he reappeared in sexual imagery as comical body parts, as in the paintings of Carroll Dunham. In all times, the human male nude has been depicted primarily by male artists. Even during the time of the second wave of feminism in the 1960’s and 70’s, when female artists began what is now commonly called “feminist art”, the subjects were predominantly female. If the nude male was depicted in this epoch, it was usually in the service of cynicism or irony.

It is my intention to create a body of work that depicts the nude male human in a way known as Einfühlung. This is the German word for empathy, or “feeling into”. The capacity of one individual to experience the needs, concerns, joys, sorrows and anxieties of another individual as if they were his or her own. The word Einfühlung was first coined by the German philosopher Robert Vischer, and was later expounded upon by Theodor Lipps, another German philosopher. Its relevance to the visual arts lies in the idea that the representation of a thing can represent not only its geometry but its feeling of being as well. The idea of representation in this way carries not only a feeling component but also a cognitive component.

It is in this aspect that I wish to contribute to the existing work depicting the male nude. That is, from the perspective of a female who has experienced the male body and psyche from the vantage point of being a child, lover, mother, friend, colleague, confidant, wife and healer of men. This is a unique perspective from which to view the nude male and attempt to communicate the perceived body—a body containing the full range of human emotion that for so long has been denied men in their life, in social convention and in the visual arts.

The earliest images of the human body, dating back to pre-historic time, were images of woman. These images made by Paleolithic peoples some 25,000 years ago reflected their cultural beliefs and values (Eisler). Presumably these figures represented societies where the female was venerated either as leader or giver of life (Eisler, Stone). The Venus of Willendorf was one such work of “art”, as were wall paintings, cave sanctuaries and burial sites. All were concerned with the mysteries of life and death. Following this are the images from Neolithic times, where goddess figures were found in widespread archeological sites from India and the Middle East to Europe. (Lecture). Some 6000 years B.C.E. on the Island of Crete, Minoan art still spoke of a culture that celebrated life and did not fear death. There were images of female deities and of the snake, which represented the circle of life and death (Higgins). There are images of the phallus in shrines to the mother goddess, but it is in Ancient Greece that the image of the phallus reaches its zenith. Eva Keuls states that the imagery of vase painting and figured monuments tell a story of a society dominated by men, and the imagery of an erect phallus indicates not sexual dominance in the private sphere of relationships but the “power of the phallus”. She goes on to make the claim that the widespread imagery of the erect penis on pottery, statues of gods, and at the entrances to both private and public architectural structures was a symbol of masculinity at the start of Western civilization indicative of a “phallocracy “or “power of the phallus” — “a cultural system symbolized by the image of the male reproductive organ in permanent erection” (Keuls). In sexual terms the rape of woman, and in political terms imperialism and patriarchy. The Classic nude of Ancient Greece was a male ideogram signifying an aesthetic ideal and asserting masculine strength. Its beauty is remote and impassive, with the archaic smile impervious to the ravages of real life, as in the Kouros. The perfect young body could signify an athlete, a hero or the god Apollo himself. The sculptor Polykleitos, in creating the Doryphoros athlete, gave tribute to the value of ideal beauty expressed mathematically with a perfectly proportioned or idealized body. The male body came to represent the idealized self-images of Athenian citizens (all of whom were male, as citizenship was a male prerogative), and the proud symbol of Greek culture. Aphrodite is the only goddess ever portrayed naked, and she had been reduced to an object of sexual desire. “The religious awe associated with the great goddess is always on the point of dwindling into a connoisseur’s pleasure in a beautiful object, into voyeurism, or into simple lust” (Walters 40).

In Greek culture the norms of society changed, and so the depiction of the male nude. He became more graceful, and art became a form that catered to personal tastes. The Greek male became more interested in family life, and woman was afforded more freedom. The image of the male became more feminized. Art began to convey how we feel in our bodies rather than the body only as a depiction of ideas. In late antique art the image of the hermaphrodite begins to appear, and most are depicted as jokes, or as an appeal to the sexually sophisticated spectator. (Walters)

Across the ensuing centuries of Western civilization the male nude has come to represent a range of political, religious and moral ideas. He is a public figure with postures and movements that denote potency, and is found in public squares, adorning buildings and churches. He has come to represent disciplined virility, as in the athlete, and in the conquests and civilization of western society. He is depicted as active in contrast to female passivity. Hercules is the archetypal phallic nude whose virility won him the status of a god in Greek mythology. In Christianity, he is a symbol of fortitude, and in the Renaissance, a symbol of manhood and political power. The phallus was also associated with tools and weapons; in our current modern political system, Republican Whip Tom Delay was known as “the Hammer”.

Christian art depicts the duality of man divided between body and soul. This was the beginning of the negation and abuse of the body, as exemplified by self-flagellation of the devout. In Christianity, despite the rejection of sexual imagery, the male nude still retained its phallic imagery by enlarging muscles and thighs, or the nude was accessorized with weapons such as swords, clubs, or bows and arrows. The male nude in Christianity is feminized in that it is shown as passive and submissive in the service of suffering. “But Church art glorifies not true passivity but masochism, submission to violence …. Christ is nailed to a phallic tree-to propitiate a vengeful patriarchal god” (Walters, 1 0).Late medieval art focuses on death and decay of the body, the transient nature of the flesh and of earthly pleasures. In addition the social problems at the time, such as poverty and the plague, were reflected in art. “Death is personified and his skeletal body has a terrible phallic energy. He lunges at us with spear or scythe or rides a great horse that tramples all in his path” (Walters).

With the Renaissance came renewed interest in depicting the nude as a classic combination of mathematics and mysticism. This is exemplified by Leonardo’s Vitruvius man. The scientific interest in the body by the artist led to the practice of dissection of the corpse. The Renaissance nude carries the duality of the idealized beauty as well as the idea of man as a poor animal doomed to die. Donatello created the young David and the old man Jeremiah. Leonardo painted the young Saint John and the emaciated Jerome. The Renaissance artist came to terms with the beauty of the body and the finality of death. The three male nudes that recur, Cupid, Narcissus and Hercules, represent the three stages of life, childhood,

adolescence and maturity, but all idealized by the artist. Michelangelo was the ultimate artist of the male nude. He depicted the male nude in the context of Christianity, imbuing him with divine power, which is phallic and paternalistic as it passes from God to Adam.

The sixteenth century brought the mannerist nude exemplified in the work of Pontormo, Rosso and Bronzino. Here the male nude is a fashion statement. It was a platform on which the artist could display his virtuosity as a painter and transform the earlier depictions of the nude while in religious context into a more sexualized and stylized image. The context may remain the same with images of Christ or scenes describing myths, but now the body is distorted, elongated and swings between Eros and death. This is court art, and many aristocrats had themselves painted nude as idealized classical gods or heroes, for example, Grand Duke Francesco as Orpheus by Bronzino.

In the seventeenth century sensuality takes center stage with the sculpture of Bernini and the paintings of Rubens. The preferred subject of Rubens was the female nude, and the male is not nude beside her but clothed. The Venus and Adonis is the exception, and here the male genitalia are covered with a cloth, and a putti’s arm on Adonis’ thigh may be a stand in for what he could not reveal. When he does depict a nude male Rubens shows him wounded or dying. This was the time of the male martyr, with depictions of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows, Bartholomew skinned alive, Lawrence grilled and John boiled in oil. Spiritual ecstasy was realized through the sadomasochistic depiction of the nude male saint in pain or the dead Christ. Caravaggio, however, turns the tables with his overtly sensuous and sexual male nudes. Both Velasquez and Rembrandt rarely painted the nude male, but when they did they introduced the common and realistic rather than idealized figure.

The figure in art became fashionably dressed in the Eighteenth century and the female figure became the dominant nude. “Male nakedness is more likely to mean embarrassing exposure” (Walters). The predominant male nude was cupid. In the second half of this century David paints the male nude in the classical Greek heroism, and his figures are stiff and formal.

By the nineteenth century the nude male had all but disappeared and the nude female became the central symbol of art. A Victorian sensibility dominated society, and so began the denial of the frailty of the human animal. The denial of death began to take hold. The duality of fear and desire was projected onto the female nude as she encompassed ideal chaste beauty and animal carnal nature. When the nude male was depicted, as by Gericault, it was with stark realism and intense attention to the physicality of the body. This forced a look at death. Other male nudes are either wrestlers or bathers, and speak of a romantic relationship with nature, such as in Courbet, Cézanne, and Eakins.

At the beginning of the Twentieth Century the nude male was completely irrelevant. The human body began to disappear as figurative art gave way to abstraction. The nude male was prominently displayed in service of German war propaganda as a heroic athlete akin to the Hellenistic ideal of beauty, and reserved for the Nordic race. The male body, in particular the penis, was a hidden subject in art of the Twentieth Century. Although the new liberalism gives free reign to erotic expression, it is most acceptable when translated through the female body. “[T]hough contemporary artists put the female body and genitals through the most fearful and drastic distortions, they tend to treat their own organs conservatively-gently, protectively” (Waters). A few male artists have treated the investigation of their own bodies with a frankness that does not involve the female, most notably Egon Schiele, Stanley Spencer and Lucien Freud. Homosexual themes have also been addressed by male artists in the modern era. Phillip Pearlstein also painted the nude male in realistic detail, but in “physical discomfort and psychic withdrawal” (Nochlin). As previously noted, male genitalia, when depicted outside of homoeroticism, are as comical body parts, for example, Caroll Dunham.

EinfühIung is a term that was invented by the German Philosopher Robert Vischner at the end of the nineteenth century. His doctoral thesis, On the Optical Sense of Form; A Contribution to Aesthetics (1873), explored the idea of idealism relative to architectural form. The word means esthetic sympathy, or “feeling-into”. The English word was coined in 1909 as “empathy”. This is recognized as the ability to recognize and share feelings. Unlike sympathy, which is feeling sad for or in agreement with, empathy implies a capacity to share feelings being experienced by another human, whether they be sadness, happiness, etc. So empathy is the prerequisite to compassion. In other words, experiencing emotions that match another’s, and blurring the line between self and other. The German philosopher Theodore Lipps furthered this idea of empathy in art, and along with his contemporary, Sigmund Freud, was a proponent of the idea of the unconscious. Some of Lipps students went on to form a new branch of philosophy known as Phenomenology of Essences.

Empathy can be thought of as having both emotional and cognitive aspects, with the intuitive as the emotional aspect and perspective-taking as the cognitive aspect. The ability to be empathetic is a human capacity hard wired in our brains as a survival mechanism. This concept has received much attention recently, and it is the focus of much neuroscientific research. On a psychological level one can distinguish the well-adjusted empathetic from the psychopath and the narcissistic personality disorder, as well as those with the autism spectrum disorders. Antonio Demasio, a prominent professor of Neurology, in his book The Feeling of What Happens; Body and Emotions in the Making of Consciousness, states “the evidence suggests that most, if not all, emotional responses are the result of a long history of evolutionary fine-tuning. Emotions are part of the bioregulatory devices with which we come equipped to survive”. In terms of art and art making, Ellen Disanayake makes the connection between the empathetic impulse and the artistic impulse in an “aesthetic empathy”.

I have produced a body of work that focuses on the male nude. I am interested in my own empathetic response to the male nude, and how as a female the duality of emotional and intuitive unconscious combines with conscious and cognitive perspective-taking to translate into an aesthetic experience. Furthermore, I am interested in the response of both males and females to my work.

The topic of my final thesis project is the specific process involved, and the relationship of my work to previous work, as well as how the work fits within the context of female and male movements, toward a greater evolution of human understanding and development outside of rigid gender stereotypes.

All the work has been done from life. This is particularly important in light of Einfuhlung, as it is only through the interaction of the living breathing model and the reacting stuggling painter that the process of empathy as it relates to art occurs. As I paint, I am acutely aware of the present life of the model. We begin with a discussion of the planned painting, and input from the model regarding the intent of the painting and the pose involved.

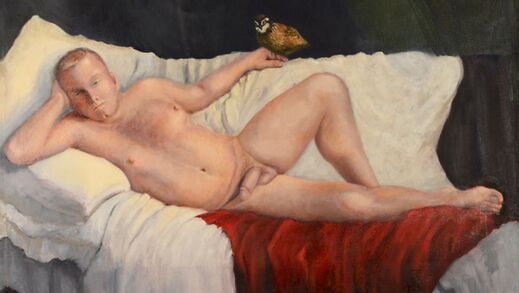

The poses and the intent of the paintings investigate the visual impact of placing men in positions in which women have historically been placed. I have looked to Courbet and the Origin of the World, and focused on a realistic depiction of male genitalia. I look to the classic reclining nude first envisioned by Giorgione and Titian, and then questioned by Manet. I look to the Three Graces, which have not only come to represent qualities assigned to females, but through painting and sculpture over the millennium, have been depicted as exclusively female.

I use thick paint with visible brush strokes to record my response to intense observation of the subjects, and not only the cognitive but also the visceral response or Einfuhlung. It is my intent to produce with paint the feeling of flesh, with its softness, its sensuality and its vulnerability. I have chosen men with particular attention to their age. I was not interested in

nubile bodies of young Adonises or those showing the ravages of advanced age, but the average man. As such, the subjects are middle aged men who are more or less average and what I would consider the “real” as opposed to the ideal man.

My interest in placing males in positions previously reserved for females is twofold: firstly, to liberate them and make room for them to be allowed the full range of emotion afforded humans without regard to gender, and secondly, to challenge the viewer’s conception of the place where men may or may not reside.

The work has been viewed by artists and non-artists of both genders. The most troubling, but not surprising, response has been the idea that the work could be read as homoerotic. This was mentioned by observers who did not know the artist’s gender and assumed that I was male. For those viewers who did know the artist there has been a variable response as to whether this was a depiction of the homosexual male(s). Both heterosexual and homosexual males have seen these nudes as both gay and straight. The same can be said of females. The male viewer more often than the female had somewhat negative reaction to the depiction of male genitalia, and this occurred more often among heterosexuals.

In conclusion, this body of work represents my investigation of the living male nude as he sits before me in imperfection, naked and vulnerable under my scrutiny. It is my attempt, with artistic Einfuhlung, to paint them as I see them: real, human, beautiful, erotic and vulnerable, and to set them free to be all that and more.

Works Cited

Bordo, Susan. The male body: a new look at men in public and in private. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Clark, Kenneth. The nude; a study in ideal form. New York: Pantheon Books, 1956.

Damasio, Antonio R. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

Damasio, Antonio R. Looking for Spinoza: joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain. Orlando, Fla.: Harcourt, 2003.

Dissanayake, Ellen. Homo aestheticus: where art comes from and why. New York: Free Press, 1992.

Keuls, Eva C. The reign of the phallus: sexual politics in ancient Athens. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Male trouble: a crisis in representation. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Stone, Merlin. When God was a woman. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

New York University. “The Lost World of Old Europe, The Danube Valley, 5000-3500BC.The lost world of old Europe, the study of the ancient world, Institute for Ancient Studies Lecture Series, New York University, 15 East 84th St, New York, N.Y., 15 Nov. 2010. Lecture.

Eisler, Raine. The chalice and the blade: our history, your future. New York: Harper Collins, 1987.

Higgins, Reynold. Minoan and Mycenean Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1967.

Mirzoeff, N. The visual cultural reader. London: Routledge, 1998.

Nochlin, Linda. The art of Phillip Perlstein. Georgia: Georgia Museum of Art, 1970.

Walters,Margaret . The nude male. New York and London: Paddington Press, 1978. Linda Andrei

1

The nude male has been present in the visual arts, at least since the time of Greek culture, in both painting and sculpture. He has been depicted as a heroic figure, a mythological figure, a warrior, a mischievous sexual adventurer, and at times a tragic suffering victim of oppression. In each case he is usually anatomically idealized with prominent musculature, and in almost all cases he is depicted as active—either engaged in some heroic activity where his physical prowess is brought into play, or about to be realized. Even when depicted in chains he is, as a human animal, shown as strong and active. When the nude male is in contemplation he is still in an active process, and interestingly he is still adorned with idealized musculature. This leads one to believe that the very essence of maleness requires the development of a well toned physique. Most of the time the nude has been used to convey an idea or a feeling, and both genders have been included in this pursuit. However, the nude male began to disappear from the visual arts around the turn of the 19th or early 20th century. In the second half of the 20th century he reappeared in sexual imagery as comical body parts, as in the paintings of Carroll Dunham. In all times, the human male nude has been depicted primarily by male artists. Even during the time of the second wave of feminism in the 1960’s and 70’s, when female artists began what is now commonly called “feminist art”, the subjects were predominantly female. If the nude male was depicted in this epoch, it was usually in the service of cynicism or irony.

It is my intention to create a body of work that depicts the nude male human in a way known as Einfühlung. This is the German word for empathy, or “feeling into”. The capacity of one individual to experience the needs, concerns, joys, sorrows and anxieties of another individual as if they were his or her own. The word Einfühlung was first coined by the German philosopher Robert Vischer, and was later expounded upon by Theodor Lipps, another German philosopher. Its relevance to the visual arts lies in the idea that the representation of a thing can represent not only its geometry but its feeling of being as well. The idea of representation in this way carries not only a feeling component but also a cognitive component.

It is in this aspect that I wish to contribute to the existing work depicting the male nude. That is, from the perspective of a female who has experienced the male body and psyche from the vantage point of being a child, lover, mother, friend, colleague, confidant, wife and healer of men. This is a unique perspective from which to view the nude male and attempt to communicate the perceived body—a body containing the full range of human emotion that for so long has been denied men in their life, in social convention and in the visual arts.

The earliest images of the human body, dating back to pre-historic time, were images of woman. These images made by Paleolithic peoples some 25,000 years ago reflected their cultural beliefs and values (Eisler). Presumably these figures represented societies where the female was venerated either as leader or giver of life (Eisler, Stone). The Venus of Willendorf was one such work of “art”, as were wall paintings, cave sanctuaries and burial sites. All were concerned with the mysteries of life and death. Following this are the images from Neolithic times, where goddess figures were found in widespread archeological sites from India and the Middle East to Europe. (Lecture). Some 6000 years B.C.E. on the Island of Crete, Minoan art still spoke of a culture that celebrated life and did not fear death. There were images of female deities and of the snake, which represented the circle of life and death (Higgins). There are images of the phallus in shrines to the mother goddess, but it is in Ancient Greece that the image of the phallus reaches its zenith. Eva Keuls states that the imagery of vase painting and figured monuments tell a story of a society dominated by men, and the imagery of an erect phallus indicates not sexual dominance in the private sphere of relationships but the “power of the phallus”. She goes on to make the claim that the widespread imagery of the erect penis on pottery, statues of gods, and at the entrances to both private and public architectural structures was a symbol of masculinity at the start of Western civilization indicative of a “phallocracy “or “power of the phallus” — “a cultural system symbolized by the image of the male reproductive organ in permanent erection” (Keuls). In sexual terms the rape of woman, and in political terms imperialism and patriarchy. The Classic nude of Ancient Greece was a male ideogram signifying an aesthetic ideal and asserting masculine strength. Its beauty is remote and impassive, with the archaic smile impervious to the ravages of real life, as in the Kouros. The perfect young body could signify an athlete, a hero or the god Apollo himself. The sculptor Polykleitos, in creating the Doryphoros athlete, gave tribute to the value of ideal beauty expressed mathematically with a perfectly proportioned or idealized body. The male body came to represent the idealized self-images of Athenian citizens (all of whom were male, as citizenship was a male prerogative), and the proud symbol of Greek culture. Aphrodite is the only goddess ever portrayed naked, and she had been reduced to an object of sexual desire. “The religious awe associated with the great goddess is always on the point of dwindling into a connoisseur’s pleasure in a beautiful object, into voyeurism, or into simple lust” (Walters 40).

In Greek culture the norms of society changed, and so the depiction of the male nude. He became more graceful, and art became a form that catered to personal tastes. The Greek male became more interested in family life, and woman was afforded more freedom. The image of the male became more feminized. Art began to convey how we feel in our bodies rather than the body only as a depiction of ideas. In late antique art the image of the hermaphrodite begins to appear, and most are depicted as jokes, or as an appeal to the sexually sophisticated spectator. (Walters)

Across the ensuing centuries of Western civilization the male nude has come to represent a range of political, religious and moral ideas. He is a public figure with postures and movements that denote potency, and is found in public squares, adorning buildings and churches. He has come to represent disciplined virility, as in the athlete, and in the conquests and civilization of western society. He is depicted as active in contrast to female passivity. Hercules is the archetypal phallic nude whose virility won him the status of a god in Greek mythology. In Christianity, he is a symbol of fortitude, and in the Renaissance, a symbol of manhood and political power. The phallus was also associated with tools and weapons; in our current modern political system, Republican Whip Tom Delay was known as “the Hammer”.

Christian art depicts the duality of man divided between body and soul. This was the beginning of the negation and abuse of the body, as exemplified by self-flagellation of the devout. In Christianity, despite the rejection of sexual imagery, the male nude still retained its phallic imagery by enlarging muscles and thighs, or the nude was accessorized with weapons such as swords, clubs, or bows and arrows. The male nude in Christianity is feminized in that it is shown as passive and submissive in the service of suffering. “But Church art glorifies not true passivity but masochism, submission to violence …. Christ is nailed to a phallic tree-to propitiate a vengeful patriarchal god” (Walters, 1 0).Late medieval art focuses on death and decay of the body, the transient nature of the flesh and of earthly pleasures. In addition the social problems at the time, such as poverty and the plague, were reflected in art. “Death is personified and his skeletal body has a terrible phallic energy. He lunges at us with spear or scythe or rides a great horse that tramples all in his path” (Walters).

With the Renaissance came renewed interest in depicting the nude as a classic combination of mathematics and mysticism. This is exemplified by Leonardo’s Vitruvius man. The scientific interest in the body by the artist led to the practice of dissection of the corpse. The Renaissance nude carries the duality of the idealized beauty as well as the idea of man as a poor animal doomed to die. Donatello created the young David and the old man Jeremiah. Leonardo painted the young Saint John and the emaciated Jerome. The Renaissance artist came to terms with the beauty of the body and the finality of death. The three male nudes that recur, Cupid, Narcissus and Hercules, represent the three stages of life, childhood,

adolescence and maturity, but all idealized by the artist. Michelangelo was the ultimate artist of the male nude. He depicted the male nude in the context of Christianity, imbuing him with divine power, which is phallic and paternalistic as it passes from God to Adam.

The sixteenth century brought the mannerist nude exemplified in the work of Pontormo, Rosso and Bronzino. Here the male nude is a fashion statement. It was a platform on which the artist could display his virtuosity as a painter and transform the earlier depictions of the nude while in religious context into a more sexualized and stylized image. The context may remain the same with images of Christ or scenes describing myths, but now the body is distorted, elongated and swings between Eros and death. This is court art, and many aristocrats had themselves painted nude as idealized classical gods or heroes, for example, Grand Duke Francesco as Orpheus by Bronzino.

In the seventeenth century sensuality takes center stage with the sculpture of Bernini and the paintings of Rubens. The preferred subject of Rubens was the female nude, and the male is not nude beside her but clothed. The Venus and Adonis is the exception, and here the male genitalia are covered with a cloth, and a putti’s arm on Adonis’ thigh may be a stand in for what he could not reveal. When he does depict a nude male Rubens shows him wounded or dying. This was the time of the male martyr, with depictions of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows, Bartholomew skinned alive, Lawrence grilled and John boiled in oil. Spiritual ecstasy was realized through the sadomasochistic depiction of the nude male saint in pain or the dead Christ. Caravaggio, however, turns the tables with his overtly sensuous and sexual male nudes. Both Velasquez and Rembrandt rarely painted the nude male, but when they did they introduced the common and realistic rather than idealized figure.

The figure in art became fashionably dressed in the Eighteenth century and the female figure became the dominant nude. “Male nakedness is more likely to mean embarrassing exposure” (Walters). The predominant male nude was cupid. In the second half of this century David paints the male nude in the classical Greek heroism, and his figures are stiff and formal.

By the nineteenth century the nude male had all but disappeared and the nude female became the central symbol of art. A Victorian sensibility dominated society, and so began the denial of the frailty of the human animal. The denial of death began to take hold. The duality of fear and desire was projected onto the female nude as she encompassed ideal chaste beauty and animal carnal nature. When the nude male was depicted, as by Gericault, it was with stark realism and intense attention to the physicality of the body. This forced a look at death. Other male nudes are either wrestlers or bathers, and speak of a romantic relationship with nature, such as in Courbet, Cézanne, and Eakins.

At the beginning of the Twentieth Century the nude male was completely irrelevant. The human body began to disappear as figurative art gave way to abstraction. The nude male was prominently displayed in service of German war propaganda as a heroic athlete akin to the Hellenistic ideal of beauty, and reserved for the Nordic race. The male body, in particular the penis, was a hidden subject in art of the Twentieth Century. Although the new liberalism gives free reign to erotic expression, it is most acceptable when translated through the female body. “[T]hough contemporary artists put the female body and genitals through the most fearful and drastic distortions, they tend to treat their own organs conservatively-gently, protectively” (Waters). A few male artists have treated the investigation of their own bodies with a frankness that does not involve the female, most notably Egon Schiele, Stanley Spencer and Lucien Freud. Homosexual themes have also been addressed by male artists in the modern era. Phillip Pearlstein also painted the nude male in realistic detail, but in “physical discomfort and psychic withdrawal” (Nochlin). As previously noted, male genitalia, when depicted outside of homoeroticism, are as comical body parts, for example, Caroll Dunham.

EinfühIung is a term that was invented by the German Philosopher Robert Vischner at the end of the nineteenth century. His doctoral thesis, On the Optical Sense of Form; A Contribution to Aesthetics (1873), explored the idea of idealism relative to architectural form. The word means esthetic sympathy, or “feeling-into”. The English word was coined in 1909 as “empathy”. This is recognized as the ability to recognize and share feelings. Unlike sympathy, which is feeling sad for or in agreement with, empathy implies a capacity to share feelings being experienced by another human, whether they be sadness, happiness, etc. So empathy is the prerequisite to compassion. In other words, experiencing emotions that match another’s, and blurring the line between self and other. The German philosopher Theodore Lipps furthered this idea of empathy in art, and along with his contemporary, Sigmund Freud, was a proponent of the idea of the unconscious. Some of Lipps students went on to form a new branch of philosophy known as Phenomenology of Essences.

Empathy can be thought of as having both emotional and cognitive aspects, with the intuitive as the emotional aspect and perspective-taking as the cognitive aspect. The ability to be empathetic is a human capacity hard wired in our brains as a survival mechanism. This concept has received much attention recently, and it is the focus of much neuroscientific research. On a psychological level one can distinguish the well-adjusted empathetic from the psychopath and the narcissistic personality disorder, as well as those with the autism spectrum disorders. Antonio Demasio, a prominent professor of Neurology, in his book The Feeling of What Happens; Body and Emotions in the Making of Consciousness, states “the evidence suggests that most, if not all, emotional responses are the result of a long history of evolutionary fine-tuning. Emotions are part of the bioregulatory devices with which we come equipped to survive”. In terms of art and art making, Ellen Disanayake makes the connection between the empathetic impulse and the artistic impulse in an “aesthetic empathy”.

I have produced a body of work that focuses on the male nude. I am interested in my own empathetic response to the male nude, and how as a female the duality of emotional and intuitive unconscious combines with conscious and cognitive perspective-taking to translate into an aesthetic experience. Furthermore, I am interested in the response of both males and females to my work.

The topic of my final thesis project is the specific process involved, and the relationship of my work to previous work, as well as how the work fits within the context of female and male movements, toward a greater evolution of human understanding and development outside of rigid gender stereotypes.

All the work has been done from life. This is particularly important in light of Einfuhlung, as it is only through the interaction of the living breathing model and the reacting stuggling painter that the process of empathy as it relates to art occurs. As I paint, I am acutely aware of the present life of the model. We begin with a discussion of the planned painting, and input from the model regarding the intent of the painting and the pose involved.

The poses and the intent of the paintings investigate the visual impact of placing men in positions in which women have historically been placed. I have looked to Courbet and the Origin of the World, and focused on a realistic depiction of male genitalia. I look to the classic reclining nude first envisioned by Giorgione and Titian, and then questioned by Manet. I look to the Three Graces, which have not only come to represent qualities assigned to females, but through painting and sculpture over the millennium, have been depicted as exclusively female.

I use thick paint with visible brush strokes to record my response to intense observation of the subjects, and not only the cognitive but also the visceral response or Einfuhlung. It is my intent to produce with paint the feeling of flesh, with its softness, its sensuality and its vulnerability. I have chosen men with particular attention to their age. I was not interested in

nubile bodies of young Adonises or those showing the ravages of advanced age, but the average man. As such, the subjects are middle aged men who are more or less average and what I would consider the “real” as opposed to the ideal man.

My interest in placing males in positions previously reserved for females is twofold: firstly, to liberate them and make room for them to be allowed the full range of emotion afforded humans without regard to gender, and secondly, to challenge the viewer’s conception of the place where men may or may not reside.

The work has been viewed by artists and non-artists of both genders. The most troubling, but not surprising, response has been the idea that the work could be read as homoerotic. This was mentioned by observers who did not know the artist’s gender and assumed that I was male. For those viewers who did know the artist there has been a variable response as to whether this was a depiction of the homosexual male(s). Both heterosexual and homosexual males have seen these nudes as both gay and straight. The same can be said of females. The male viewer more often than the female had somewhat negative reaction to the depiction of male genitalia, and this occurred more often among heterosexuals.

In conclusion, this body of work represents my investigation of the living male nude as he sits before me in imperfection, naked and vulnerable under my scrutiny. It is my attempt, with artistic Einfuhlung, to paint them as I see them: real, human, beautiful, erotic and vulnerable, and to set them free to be all that and more.

Works Cited

Bordo, Susan. The male body: a new look at men in public and in private. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

Clark, Kenneth. The nude; a study in ideal form. New York: Pantheon Books, 1956.

Damasio, Antonio R. The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1999.

Damasio, Antonio R. Looking for Spinoza: joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain. Orlando, Fla.: Harcourt, 2003.

Dissanayake, Ellen. Homo aestheticus: where art comes from and why. New York: Free Press, 1992.

Keuls, Eva C. The reign of the phallus: sexual politics in ancient Athens. New York: Harper & Row, 1985.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Male trouble: a crisis in representation. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Stone, Merlin. When God was a woman. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

New York University. “The Lost World of Old Europe, The Danube Valley, 5000-3500BC.The lost world of old Europe, the study of the ancient world, Institute for Ancient Studies Lecture Series, New York University, 15 East 84th St, New York, N.Y., 15 Nov. 2010. Lecture.

Eisler, Raine. The chalice and the blade: our history, your future. New York: Harper Collins, 1987.

Higgins, Reynold. Minoan and Mycenean Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1967.

Mirzoeff, N. The visual cultural reader. London: Routledge, 1998.

Nochlin, Linda. The art of Phillip Perlstein. Georgia: Georgia Museum of Art, 1970.

Walters,Margaret . The nude male. New York and London: Paddington Press, 1978. Linda Andrei

1